Imagine your school is traveling to Athens to play the University of Georgia in football. Here’s the catch: you have to play by Georgia’s rules. In the early days of college football, each school developed its own rules–in intercollegiate contests, the home team’s rules prevailed. The early days of college football were a time of trial and error. Different schools played different versions of the game. Some versions looked more like soccer, others like rugby, and others were a combination of many influences.

During the 1820s, several colleges in the northeast played their own version of college football. Each had its own set of rules and played only intramural games. For example, Princeton played a game called “ballown” as early as 1820. Harvard began its own version in 1827 with a game between the freshmen and sophomore classes affectionately known as “Bloody Monday,” while Dartmouth played something called “Old Division Football.” These disparate games had some basic features in common: large numbers of players trying to advance a ball into a goal by any means necessary, violence, and frequent injury. Because of the injury issue, these schools abolished their brand of football by the beginning of the Civil War, although the game continued in some form at various east coast prep schools.

By the late 1860s, football had returned to colleges in the northeast. On November 6, 1869, Rutgers and Princeton played the first intercollegiate football game. The schools played with a round ball under Rutgers’ rules. One score equaled one point. The game appeared more similar to rugby and soccer than to the American football of today. Each side played with 25 players with the objective of kicking a ball into the opposing team’s goal. Players were not allowed to throw or carry the ball, and physical contact was part of the game. Rutgers defeated the visitors from Princeton 6-4. A week later the two schools played at Princeton under Princeton’s rules. The rules of the two schools were similar with the notable exception that a player who caught a ball on the fly was awarded a free-kick. Princeton scored a measure of revenge with an 8-0 victory.

As more colleges began playing football, school officials quickly saw the need for standardized rules. On October 20, 1873, representatives from Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Rutgers met in New York to develop a set of regulations based more on soccer than rugby. Harvard boycotted the meeting because it insisted on playing by its own regulations known as the “Boston game” – a version predicated more on carrying the ball than on kicking it. Harvard found itself without competition until Tufts College, located outside of Boston, agreed to play Harvard June 4, 1875. Tufts won a passionate game 1-0.

In 1876, Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia met in New York to try once more to standardize the rules. This time the schools agreed on a new code of regulations based largely on the Rugby Football Union’s code from England. Under the new rules, a two-point touchdown replaced the kicked goal as the primary means of scoring.

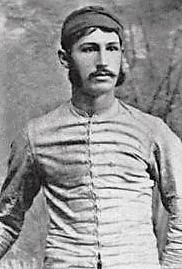

It wasn’t until 1880 that college football began to resemble the game as it is played today. Walter Camp was a college football player (Yale), coach (Yale and Stanford), and sportswriter. As Yale coach, his 1888, 1891, and 1892 teams won recognition as national champions. Camp also took part in the various intercollegiate rules committees beginning as a player in 1880 until his death in 1925. Because of his role on the rules committees, Camp became known as the “Father of American football.” Camp spearheaded the change to today’s game. At yet another New York meeting, Camp convinced representatives of Yale, Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia to approve a reduction from 15 to 11 players per side, the establishment of a line of scrimmage, and the snap of the ball between the center and the quarterback. Football became more of an open game emphasizing speed.

At later meetings, Camp helped persuade the schools that a team had to gain five yards within three downs or lose possession; that the field should be reduced in size to its modern dimensions of 120 yards by 53.3 yards; and that four points should be awarded for a touchdown, two points for kicks made after touchdowns, two points for safeties, and five for field goals. (The scoring structure has since been changed to six points for touchdowns, one for the kick after a touchdown, and three for a successful field goal.) Camp was also responsible for having two paid officials referee every game and legalizing tackling below the waist.

College football owes much to pioneers of the game like Walter Camp. Without standardization of the rules, the mixed bag of a game that evolved into what we now call football would likely not have survived.